What exactly is a twist? And how can you write a truly effective twist without spelling it out for the reader?

When I was in the sixth grade, one of our reading assignments was the screenplay for The Twilight Zone episode "The Monsters are Due on Maple Street". The unusual plot and satisfying twist captivated me, so much so that I binge-watched the entire series before binge-watching was a marketable term. I was absolutely enchanted with the show's writing: it was so elegantly creepy, so minimalist and anxiety-inducing. And, of course, I fell in love with twists. Up until that point in my life, most of the media that I consumed was largely predictable and dependent on conventional storytelling. The ennui endemic to reading nothing but children and tween fare was blasted away by The Twilight Zone, which inspired me to write my own psychological thrillers (which invariably included someone awakening from a coma and realizing she is a different person, a la "A World of Difference"). Being exposed to the series showed me how clever writing can strengthen a story and how a twist can, well, make a world of difference.

This isn't to say that I want every story that I read or write to contain a twist. Some stories are meant to have a more linear progression. Poorly written or badly executed twists can derail plots or even nullify the story that came before it. Even an obvious twist might disengage the audience. If you don't have confidence in your twist, then I'd advise abandoning it. Twists might be interesting, but they aren't entirely necessary, especially if your work is supported by strong characters and robust conflicts. If story and plot are the foundation of your work, twists are like the shutters or crenelation--pretty and distinguishing, but not essential to the structure.

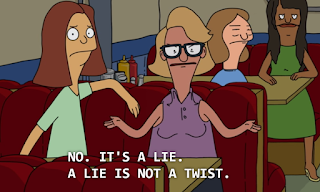

However, if your story features a twist that is integral to the plot, then there are some steps that can be undertaken to ensure that the twist is strong enough to keep the screws and pins of the story in place. The first is more of a personal irritation, but I'm sure that the movie-going masses will agree. Please try to construct an original twist. PLEASE. Or, at the very least, create an intriguing variation on a cliche and pair it with unconventional circumstances (some horror movies can get away with a predictable twist if it has a fresh perspective on the twist or can express it through unusual techniques). It can be difficult to concoct a twist of your own, especially with the over-saturation of "twist"-films in the media (what could possibly befall this white family of five that has decided to seek a "fresh start" in a decrepit mansion in the countryside? Surely, you will never be able to guess what those thumps are!), but if you're willing to examine a tired trope from a new angle, you might be able to create something new and invigorating. Take the 2011 film Insidious: a white family has just moved into a new house and there are strange noises and faces in the darkness! There must be a demon in the house! So, the family actually makes a logical decision--they move to a new house. And the haunting follows them. Now that is an exciting, refreshing twist on a twist: the "ghost" is with the family, not the house (it's not technically a ghost, but I've already spoiled enough the film. If you haven't watched it, I highly recommend it.)

Once you've got your twist, you have to plan your story around it. Like the ending to your story, the twist has to be established before you begin and considered a proverbial destination for your story to reach. While a good twist should surprise the reader, there is no harm in using foreshadowing and other premonitory elements to support the twist. In fact, utilizing subtle hints can strengthen the twist and imbue it with the potency that will make it memorable. Most audiences didn't see the ending to The Sixth Sense coming (not even my terrifyingly observant mother, who I use as the yardstick against which all good twists should be measured), but upon reviewing the film, they saw the clues and realized that the twist had been as obvious as... well, a bright red balloon. M. Night Shyamlan received adulation for his incredible twist, which was supported by a red herring (literally and metaphorically), clever visual cues, and a poignancy uncommon in movies of the genre (the emotional dexterity of the film is even more astonishing compared to the emotional... absence of The Happening). It is obvious from the beginning of the movie that this entire film is planned around its twist. And that, combined with the aforementioned techniques, makes it one of the most memorable in history.

Not every twist needs to be quite as monumental as those presented in films like The Sixth Sense and Abre Los Ojos (the Spanish movie that Cameron Crowe's Vanilla Sky is based on. I recommend the original.) In fact, twists do not have to be reserved for the ending of a piece of work. Certainly, twist endings are a staple of short fiction ("The Boogeyman" being the best example. No, Stephen King is not paying me to reference his work in every blog post. Yes, I swear.), but in longer works, a twist can occur at any point. A twist in the middle of a story usually denotes a major shift in atmosphere, tone, or even plot. I'm sure you've read books that start out a certain way, then go in a completely different direction after a major twist.

There is a method to these mid-story twists. The hints often have to be even subtler than those used for a finale twist, as mid-story twists usually come as more of a shock than those at the end of a story. I suggest depending more on tone and composition than imagery and blatant foreshadowing for these twists, especially as you approach the twist in question: this will eke unease out of the reader that he or she will not be able to place until he or she reaches the twist. A great example of a mid-story twist is the film The Descent (I apologize for the lack of textual examples, I haven't read a book for pleasure in months). It follows a group of women as they explore a network of underground caverns, which is terrifying enough (seriously, if you have claustrophobia, this may not be the film for you), and eventually find themselves confronting a horrifying presence. The twist is this movie is so sudden and startling that it gives the watcher whiplash. There were a few minor clues that suggested the presence of something unusual in the caverns, but so much focus was devoted to the women's struggles and the perils of their trip that these moments were quickly forgotten. From that point on, everything about the film is different: the atmosphere, the imagery and color scheme, even the score. The twist is what connects the movie, what makes it so memorable and allows it to go from an unusually claustrophobic Lifetime film to a excruciatingly visceral thriller. What might have been a subpar horror flick is made exponentially better by a strong opening (starting a twist-centric movie or story with an emotional beginning is a good move and will help invest readers or watchers in the story), a red herring first-half that would have been an interesting movie by itself, and--of course--an incredible twist.

Well, now that I've run out of movies to reference, I think it's time to bring our discussion to a close. To review: twists are intriguing and thought-provoking additions to pieces of work that can strengthen a plot, make memorable observations, and tell an incredible story. Your job as a writer is to invert a hackneyed twist or invent one of your own, and present it in an engaging, entertaining manner, as well as artfully weave foreshadowing and hints into the narrative to imbue your twist with enough gravitas to validate its existence. If you're struggling to write a twist-centered story, I'd advise watching a couple episodes of The Twilight Zone or one of the movies recommended in this post. Seeing a twist in action will help you visually place where certain cues should be included and hear how dialogue can be used as a tool in foreshadowing. Not all of us can be Rod Serling or M. Night Shymalan (not that most of us want us to be him), but with a little practice and reference material, you too can throw that twist out of left field and leave your reader spellbound.

0 comments:

Post a Comment